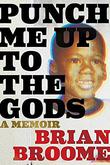

Punch Me Up to the Gods (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, May 18) opens with author Brian Broome watching a Black father and son at a bus stop. The toddler falls headfirst on the sidewalk, and the father yells at the wailing boy, “Stop cryin’….Be a man, Tuan!” Broome writes, “I am witnessing the playing out of one of the very conditions that have dogged my entire existence: this ‘being a man’ to the exclusion of all things.” The memoir details Broome’s coming-of-age as a dark-skinned gay man in Ohio and Pennsylvania and the ways his father’s and others’ beliefs about Black beauty and masculinity denied and shaped him. Punch Me Up to the Gods earned a rave from our reviewer: “Beautifully written, this examination of what it means to be Black and gay in America is a must-read.” Here we talk with Broome, 51, about heroism, Lil Nas X, and prioritizing mental health; the conversation (conducted over email) has been edited for length and clarity.

You mention that James Baldwin isn’t your favorite writer but is your hero. Which of Baldwin’s many heroic qualities do you most admire?

My admiration for James Baldwin extends far beyond the page. I have spent countless hours watching video clips of him on YouTube. I have watched him speak truth to power as if he wasn’t afraid of anyone. I don’t know if I believe that he was actually unafraid. He had to have been scared sometimes, right? But he rarely seemed it. I marvel at how he was hardly ever rattled or at a loss for words. He stood in the power of truth, and the truth was enough to keep him standing there. I hope someday to be as strong as he was.

In the introduction to Punch Me Up to the Gods, poet and artist Yona Harvey says that your “unapologetic recollections of the past—some of them cringeworthy—liberate us to view our pasts as well.” Why do you think an author’s painful recollections help readers process their own?

I think that other humans’ recounting their painful recollections out loud is a great service to others. When I went to rehab, I was full of secrets and lies, and the shame of those secrets and lies kept me sick. I used to misrepresent who I was with enormous whoppers.…In one of my first group sessions in rehab, the counselor introduced himself. His last name was Graham. He told us—a group of strangers—that he used to tell people he was a millionaire because his family invented graham crackers. He laughed about it, but I sat there with my mouth agape because I couldn’t believe he was admitting to such a grandiose lie.

I think that other humans’ recounting their painful recollections out loud is a great service to others. When I went to rehab, I was full of secrets and lies, and the shame of those secrets and lies kept me sick. I used to misrepresent who I was with enormous whoppers.…In one of my first group sessions in rehab, the counselor introduced himself. His last name was Graham. He told us—a group of strangers—that he used to tell people he was a millionaire because his family invented graham crackers. He laughed about it, but I sat there with my mouth agape because I couldn’t believe he was admitting to such a grandiose lie.

It was the same kind of lie I used to tell. In that moment, I knew that if I was going to get better, I’d have to start telling people the truth. I’d have to tell them that because of my background—where I’m from, who I’m from—I used to think that I was the lowest of the low. I used to believe that I had to compensate for my Blackness and the fact that I come from a poor family.…I thought if Mr. Graham could admit to such a thing, so could I. There’s a James Baldwin quote I like: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.” Now I don’t believe that there is anything that I’ve ever done that is singular in its cringeworthiness. I am not special. Most of us aren’t.

You describe being on a Pittsburgh bus when Jovan, a beautiful regular at the gay clubs, is queer bashed. He manages to escape, and he delivers a “Fuck you!” to the young men who beat him and also to you for not intervening. The book feels like an apology to him and a way to support future Jovans.

I recently watched the controversial music video by Lil Nas X “MONTERO (Call Me by Your Name).” In the video, he pole dances, wears high heels, and, toward the end, gives Satan a lap dance. I was surprised by my immediate reaction. It made me uncomfortable. I realized the discomfort was the same feeling I had when I was on that bus with Jovan. This feeling that he shouldn’t be dressed that way and acting that way because it will make “all of us” look bad. I felt the feeling rising up in me that as part of the “out group,” we should be doing everything we can to act “normal” and nonthreatening. I thought that I had eradicated this feeling within me, but it’s buried deep, and it still rears its ugly head from time to time. I recognize that it is my duty to fight this shame with everything I have every time it shows itself. So yes—the book is an apology to all the Jovans of the world, because they possess a strength that most people don’t. The strength to be yourself no matter what anyone else says. I still struggle with this.

Your attempt at heterosexuality failed hilariously (“Every time I look down you lookin’ at my pussy like it’s made out of math,” one woman said to you). Was it hard to find a balance of humor and devastation?

It’s not hard to see the humor in retrospect. At the time, I thought I was going to die of embarrassment. But everyone has a story like that. It helps that I’m still great friends with the woman in that story, and we’re able to laugh about who I was at the time and how young we were. There are moments of humor embedded in personal devastation, but they’re always easier to spot after the fact. For me, the balance is struck only after I pull back far enough to see the bigger picture. When writing about my attempt at heterosexuality, I had to stop thinking about how embarrassed I was and simply read the room. Something genuinely hilarious was happening in that room.

Near the end of the memoir, you say, “I have only recently begun to factor my mental health into the act of living.” How are you doing that, and how has the pandemic affected that practice?

I see a therapist regularly. I take my medications. I think that doing these things for yourself is unusual for men and, specifically, for Black men. We have always been taught to “walk it off” or “rub some dirt in it” when it comes to our pain. I realize that I wasn’t doing either. I was just covering the pain up with booze and drugs and sex, and by doing so I hurt a lot of other people. I try to be self-reflective because I believe that recognizing that my life isn’t really the center of anything helps me to become a better person.…The pandemic has given me time alone that I hadn’t planned for. It has forced me to sit with myself without the option of calling up a friend to go to a noisy restaurant.…It’s shown me how fortunate I am.

Karen Schechner is the vice president of Kirkus Indie.