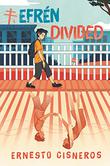

In Ernesto Cisneros’ moving debut, Efrén Divided (Harper/HarperCollins, March 31), Mexican American 12-year-old Efrén Nava tries to be a loyal best friend to David Warren, a White boy who’s running for student-body president as a goof—but secretly Efrén’s rooting for Jennifer Huerta. Jennifer’s mother— like Efrén’s—“no tiene papeles,” and Jennifer sees the position as a way to create change—in attitudes if not policies. Then Efrén’s Amá is suddenly deported, and now he must care for his two little siblings while Apá, also undocumented, works extra overtime in hopes of hiring a coyote. Thanks to his U.S. citizenship, it’s up to Efrén to cross into Tijuana to take Amá the money, a journey that proves transformative. We caught up with Cisneros, a middle school teacher, via Zoom from his home in Santa Ana, California. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In Efrén Divided you look at a lot of what is wrong about the United States, but you also see hope. How did you strike this balance?

I started writing this during the elections of 2016. It was really difficult not being political. There were so many things I wanted to say, but that wasn’t what the book was for. I wanted to always just remain true to the characters. There were times when the politics seeped in.

Like when Jennifer talks about Americans’ attention to chickens in cages and their inattention to children in cages. So yes, politics seeped in—beautifully.

[That] was one of the moments that I allowed myself a little bit of liberty.

[That] was one of the moments that I allowed myself a little bit of liberty.

I just wanted to open the front door. I just kept thinking, you know what, it’s a lot easier to hate people you don’t know. And I bet you a lot of people haven’t met a Latino family before, an immigrant family. So I just wrote about my family and things around me.

I had three students in 2016 who had a parent taken away. I have this blue box in my classroom [so kids can] let me know something’s going on. If a kid hasn’t turned in any homework for a week and something’s going on at home, I don’t want to be giving [them] detentions. [One boy] told me his father had been taken away over the weekend, and I didn’t know what to say. So for all the kids that are going through the same thing, I wanted to write a book to help them. And Efrén was the perfect name. I thought it was kind of like a friend, to help them. [Now] I have a better response: that they’re not alone. And that they do have a community of allies and supporters.

The trip to Tijuana had to be tough to write.

Yes, yes, I was so terribly worried about that. There’s so little representation of Mexico in the U.S. that I wanted to make sure that I showed the beauty of it as well. Because it is beautiful. We used to go there when I was a kid all the time. And we’d see the beaches, and I’d think, man, I wouldn’t mind living here. But then we’d go to the downtown, and there’d be the little children selling you things, and it was heartbreaking. I did go back [to Tijuana] to scout. The people who are staring at [Efrén] were the ones staring at me. I didn’t really make anything up.

Reading Efrén, you want so badly for Amá to make it back. Did you imagine an ending where she did?

No, no. I [knew] from Page 1: She can’t come back. Maybe 10 years ago, but right now, the way things are, you cannot do it. I had three students who were brave enough to let me know what’s going on. Imagine how many didn’t feel comfortable enough to share? I wanted to remain truthful. But I didn’t know how I was going to possibly end a middle-grade book like that. Jennifer saved the day for me. So many young people right now are already becoming activists, and I wanted Jennifer to reflect that.

Is there anything else you’d like to say?

[We talk] about the depiction of people of color and how we don’t see ourselves, I think it’s true. But if you look at Front Desk [by Kelly Yang (Levine/Scholastic, 2018)], I swear to God, you could take my family and you could replace it with hers. I think there’s a universal reality. The goal is for people to realize that we’re a lot more similar than we are different. And I [also] want the book to be a reminder for teachers. So the message is to the kids, that they’re not alone, and for teachers, that sometimes we see kids a certain way, and there’s a lot more to them.

Vicky Smith is a young readers’ editor.