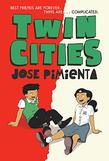

Set in the intertwined sister cities of Calexico and Mexicali along the U.S.–Mexico border, the slice-of-life Twin Cities (Random House Graphic, July 19) chronicles the home and middle school lives of twins Teresa and Fernando. When Teresa decides to continue school across the border in Calexico while Fernando commits to staying at school in Mexicali, the resulting separation of these twins—once inseparable—marks the start of the siblings’ pursuit of individual identities. For author and illustrator Jose Pimienta, this book—their second solo graphic novel—is a continuation. Whereas Suncatcher also features the city of Mexicali, wrapping up that project left Pimienta with a seed of doubt: “I had this gnawing feeling [that I didn’t get] to talk about Mexicali as much as I wanted to.”

Flavored by Pimienta’s own experiences growing up in Mexicali, Teresa’s and Fernando’s respective journeys echo and retrace one another in surprising ways. Siblinghood, after all, is complicated.

Carried out via Zoom, our conversation with Pimienta broached numerous topics, from gender expectations to the graphic novel as a format. Below are some highlights, edited for length and clarity.

As young twins, Teresa and Fernando seem more different than alike. Teresa wants to go “above and beyond” (i.e., across the border to an American school). Fernando is shy and inward, retreating into himself. This difference is mirrored in how the parents treat each kid.

It was a very deliberate choice. One of the obvious differences between these twins is that one is a boy and one is a girl. In an ideal world, kids would be treated equally, but unfortunately, that’s not really [the case]. In Mexican culture, gender roles are very set. There are these expectations for girls, for instance, that they have to be multitasking at all times, they have to be juggling multiple things, and they just have to be “ready.” Whereas with boys, they tend to have a little bit more freedom. There’s more of an inclination to accommodate to boys, unfortunately. [While working on Twin Cities,] I would think, How do I even write about this? Am I endorsing this? Am I commodifying this? Am I saying this is OK? Whether or not Teresa and Fernando verbalize it, it is what they’re experiencing. This is why Fernando has a room to himself while Teresa is dealing with not having a room. Those were very, very conscious choices in [creating] their environment.

During the first few pages, there are a couple of introductory panels where readers get different views of Mexicali. Later, the festival that Fernando and his dad attend leads to more detailed views of Mexicali. Was this depiction of the city something you wanted to ensure that you captured accurately?

I wanted to make both Mexicali and Calexico characters in the story, because it matters where this story is happening and why these cities are so important to these kids. For those opening panels, for instance, I wanted to just showcase my hometown, almost working from what comes across as a love letter to it: Like, this is what I remember; this is why I liked Mexicali so much.

I’m interested in the way you place the panels of the comic to tell two simultaneous stories. You depict one twin going about their day on one page, and the other twin doing the same on the opposing page. These passages compare the education each twin is receiving and the way they’re navigating their respective schools on their own. Is your use of panels one reason why you prefer the graphic novel format?

When you’re opening the spreads, you’re getting both stories simultaneously. That was kind of the angle for this approach. But also, it fits in with the theme of two cities, two characters. One of the other reasons why I was going with that approach is because there’s no narration throughout the book. Everything is just directly through dialogue, or whatever the main characters are saying. And the reason for that was very deliberate. If there’s going to be narration, how do you know which twin is speaking? If you throw in caption boxes, if you were to just make one single narrator, that’s an omnipresent character. So, I figured we’re going to get the story directly from the characters themselves, and it’s going to be what they are experiencing as they’re going along. I wanted to be fair to both characters. And I wanted to be as equally caring about what they’re both going through.

When you’re opening the spreads, you’re getting both stories simultaneously. That was kind of the angle for this approach. But also, it fits in with the theme of two cities, two characters. One of the other reasons why I was going with that approach is because there’s no narration throughout the book. Everything is just directly through dialogue, or whatever the main characters are saying. And the reason for that was very deliberate. If there’s going to be narration, how do you know which twin is speaking? If you throw in caption boxes, if you were to just make one single narrator, that’s an omnipresent character. So, I figured we’re going to get the story directly from the characters themselves, and it’s going to be what they are experiencing as they’re going along. I wanted to be fair to both characters. And I wanted to be as equally caring about what they’re both going through.

What three words would you use to describe Twin Cities?

I want to call it sweet. I want to call it transborderist, because it does talk about transborderism. That’s what the focus is. And I’m going to go with sibling-esque, because it is about the dynamics of siblinghood. It is about the complications of being a sibling and how that can look at a very important time in your life.

Is there anything else that you would like to mention about Twin Cities?

I tried to depict as much food as I could. Mexicali has a very specific local cuisine. While I was working on the novel, there were moments when I realized that I was drawing a lot of kids eating. In case anyone is curious, drawing someone eating is a little more difficult than you might expect! So, practice your hand gestures, and what amount of food, and what kind of food you’re drawing.

Lastly, what do you hope young readers will take away from Teresa’s and Fernando’s stories?

Middle school is hard. It’s definitely one of the most difficult times in a person’s life, or at least it was in my life. So, I hope that what readers take away is that whatever you’re experiencing is very valid, very real. And it’s OK if you don’t know how to talk about it yet. Because the book is about these two kids growing up in a border town, they're experiencing a schism and they're growing. They’re in this very transitory part of their lives. Teresa is going through her thing, and Fernando makes an interesting friend. There are all these elements that are happening. I don’t think either of them are having necessarily the easiest time on multiple things. But the way that I tried to depict it is that it is happening to them, and they’re navigating it to the best of their abilities. So, that’s what I hope that readers take away: Real life is what it is. You do your best.

J. Alejandro Mazariegos is a writer and nonprofit advocate in California.