Historical romance author Courtney Milan has been at the center of a recent controversy involving the leadership of the Romance Writers of America and her critique of the way a white author portrayed a biracial Chinese/white character.

Milan’s insights resonated with me, a Japanese/Greek reader long accustomed to either erasure or stereotyped depictions in literature. One example of the former is the use of models who are not obviously recognizably biracial on the covers of books about biracial characters—unfortunately spotted on some recent YA releases. Yes, some multiracial people can pass for just one race, and “what you look like” often lies in the eye of the beholder. But the consternation and intrusive grilling that many of us encounter while going about ordinary life indicate that we are far from invisible. These interactions often seemed tinged with an anxiety on the part of the interrogators that goes beyond normal human curiosity—as if they aren’t sure how to interact with us without a clear label.

The experiences of those who can tick more than one box are often poorly understood and presented in ways that express others’ preconceptions. Of course, the actual experiences of multiracial people vary considerably based on factors including specific ethnicities, place of residence, socio-economic status, religious affiliation, and more, but the reminders from others that we are seen as Other is a unifying force.

Lately I’ve been impressed with the appearance of #ownvoices titles that address the biracial experience in all its complexity, showing how the real problem isn’t our supposed “confusion” but efforts to pigeonhole us and that life is enriched by actively engaging with different ways of being in the world. These stories show that race, ethnicity, and culture are fluid and that transgressing society’s arbitrary labels does not make us exotic curiosities; instead it can provide valuable insights and opportunities for connection.

I Was Their American Dream, a graphic memoir written and illustrated by Malaka Gharib (Clarkson Potter, 2019), describes what it was like for her to grow up Filipina and Egyptian in multicultural California and later enter mostly white college and workplace communities. From code switching to consuming the “right” pop culture to achieve cultural legitimacy, Gharib shares her life with humor (microaggression bingo!), a quirky and original voice, and dynamic illustrations that convey a range of emotions. Teen and adult readers alike will relish it.

I Was Their American Dream, a graphic memoir written and illustrated by Malaka Gharib (Clarkson Potter, 2019), describes what it was like for her to grow up Filipina and Egyptian in multicultural California and later enter mostly white college and workplace communities. From code switching to consuming the “right” pop culture to achieve cultural legitimacy, Gharib shares her life with humor (microaggression bingo!), a quirky and original voice, and dynamic illustrations that convey a range of emotions. Teen and adult readers alike will relish it.

In Patron Saints of Nothing (Kokila, 2019), author Randy Ribay, who is Filipino and white, like his protagonist, uses a family mystery to explore male relationships, the cultural consequences of emigration and outmarriage, and the harsh drug policies of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte. Michigan teen Jay, who spends spring break in the Philippines looking for the missing cousin whose letters he stopped answering, learns as much about himself as he does about his father’s homeland in this gripping tale of growth and regret.

In Patron Saints of Nothing (Kokila, 2019), author Randy Ribay, who is Filipino and white, like his protagonist, uses a family mystery to explore male relationships, the cultural consequences of emigration and outmarriage, and the harsh drug policies of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte. Michigan teen Jay, who spends spring break in the Philippines looking for the missing cousin whose letters he stopped answering, learns as much about himself as he does about his father’s homeland in this gripping tale of growth and regret.

In All-American Muslim Girl (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019), Nadine Jolie Courtney tells the story of a girl very much like herself: Both are half Jordanian Circassian/half white American, do not “look Muslim,” and therefore have a complex relationship with both Islam and Islamophobia. This book conveys with great sincerity and heart the messiness of the high school years, from the everyday (outgrowing friendships, navigating crushes) to the specific (exploring faith, connecting with family across language barriers). It also showcases the tremendous diversity of Muslim Americans.

In All-American Muslim Girl (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019), Nadine Jolie Courtney tells the story of a girl very much like herself: Both are half Jordanian Circassian/half white American, do not “look Muslim,” and therefore have a complex relationship with both Islam and Islamophobia. This book conveys with great sincerity and heart the messiness of the high school years, from the everyday (outgrowing friendships, navigating crushes) to the specific (exploring faith, connecting with family across language barriers). It also showcases the tremendous diversity of Muslim Americans.

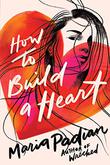

Maria Padian is third-generation American, the granddaughter of Spanish and Irish immigrants. How To Build a Heart (Algonquin, Jan. 28) presents Izzy, raised in poverty by her Puerto Rican Catholic mother after her white Methodist father’s death. It’s a sensitive take on socio-economic differences, charity and shame, prejudice and judgment, and familial love. Izzy, but not her younger brother, can pass for white, and she goes to great lengths to hide her home in a trailer park—and her rough-around-the-edges neighbor and best friend—from her wealthy schoolmates.

Maria Padian is third-generation American, the granddaughter of Spanish and Irish immigrants. How To Build a Heart (Algonquin, Jan. 28) presents Izzy, raised in poverty by her Puerto Rican Catholic mother after her white Methodist father’s death. It’s a sensitive take on socio-economic differences, charity and shame, prejudice and judgment, and familial love. Izzy, but not her younger brother, can pass for white, and she goes to great lengths to hide her home in a trailer park—and her rough-around-the-edges neighbor and best friend—from her wealthy schoolmates.

Although none of these titles reflect my specific ancestry, and they differ dramatically in setting, writing style, and storyline, I was hooked by each one of them. They made it clear how necessary it is to have works that serve as mirrors in a world that provides far too few. Equally critical is the need for kids who aren’t mixed race to go beneath the surface of appearances and gain a glimpse into the hearts and minds of their multiracial peers.

Laura Simeon is the young adult editor.