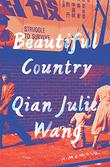

According to our reviewer, Qian Julie Wang’s debut memoir, Beautiful Country (Doubleday, Sept. 7), tells the story of “how one little girl found her way through the terror, hunger, exhaustion, and cruelty of an undocumented childhood in New York’s Chinatown…engaging readers through all five senses and the heart.” It is also Wang’s parents’ story. While both were professors in China, in the United States they did backbreaking menial labor and lived in constant terror and privation well below the poverty line. Nonetheless, after his traumatic experiences as a child during the Cultural Revolution, her father remained fiercely loyal to the “beautiful country,” which is the literal translation of Mei Guo, the Chinese word for America.

But beautiful is not the word for most of the experiences Wang describes. From the age of 7, she worked alongside her mother in a garment-industry sweatshop and in a freezing sushi factory. Starting school in second grade, she was shunted into a special ed classroom where she had to teach herself to read on her own. Nonetheless, her education culminated with a degree from Yale Law School, and she continues to work as a civil rights litigator in a firm she founded with her husband.

Though Wang interviewed her parents for the book and fact-checked portions of it with them for accuracy, she has not shown them the finished product. For that, she is waiting until publication day. She told us why in a Zoom conversation, edited here for length and clarity.

You explain in Beautiful Country that the stories it recounts were kept secret for decades.

Both my parents and I felt so much shame about our past that we never spoke about it, and I never even thought about it to myself. But when I became a naturalized citizen in 2016, actually at the moment President Barack Obama opened his video message with, “Greetings, fellow Americans,” everything changed for me. Later that year, watching the presidential debates and hearing the national discourse on immigration, I no longer thought, “Oh my God, I’m part of this group; I have to keep lying and pretending that it didn’t happen.” Suddenly, I was privileged and had a responsibility to live up to that. I had the choice to speak up while others still do not.

You were working as a lawyer at that time, right?

Yes, so I started writing using the Notes app on the subway on my way to work. There was so much that had been buried for so long. It took a lot of therapy, a lot of crying, a lot of pulling out old diaries and photos. I didn’t really think I was writing a book, but I thought maybe my future children and grandchildren would want to know where they came from. But, lo and behold, at the end of 2019 I opened the folder where I was backing up those notes and had 300 pages.

And then what?

I had to take a break from writing because my time was tied up making partner at my law firm and planning my wedding. I was getting four hours of sleep a night—something had to give. A year and a half later, on the flight to my honeymoon in September 2019, I decided it was time to go back to it. I started writing right there on the plane. I told myself to either finish by the end of the year or give up entirely.

I still had about half the book left to write—mostly the painful parts. I was so worried about my parents, how they would feel reading it, how they would react to finding these stories out in the world. The only way I could finish was to pretend that no one else would ever read it.

Your parents are citizens too, right?

They are both legal now, but they live in constant fear of ICE [U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement] banging down their door. It is a feeling that I relate to because I still have it, too. When I went to receive my COVID vaccine and they asked to see ID, I immediately had the impulse to run out the door.

They are both legal now, but they live in constant fear of ICE [U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement] banging down their door. It is a feeling that I relate to because I still have it, too. When I went to receive my COVID vaccine and they asked to see ID, I immediately had the impulse to run out the door.

I plan to give my parents a copy of the book the day it becomes public. That way, there’s no counting down in terror to the day they’re sure ICE is coming to get us. It will be too late to worry. I’m hoping that it will help them find some healing and closure and permission to forgive themselves.

My mother Googles me all the time. She’s watched every interview and read all my op-eds, and I think that’s helped her get used to it. This weekend she actually got me a mug which says, “Please do not annoy the writer. She may put you in a book and kill you.”

Tell us about the op-eds.

I wrote about the Supreme Court decision on DACA for the New York Times, and then this February, I did a piece on anti-Asian racism. So many people were shocked by the resurgence of hate during COVID, but for us, it’s nothing new. Chink was among the first English words I learned, and I’ve never been in a public space in the United States without some fear for my bodily safety. Throughout the pandemic, my parents were hesitant to go outside at all. When they had to, they wore hats, sunglasses, and double masks to avoid being recognized as Asian.

Once you finished the manuscript, how did you look for an agent?

With Google [laughs]. I must have sent out 60 query letters—some of them probably to people who didn’t even represent adult books. But I really had no idea what I was doing. Fortunately, I also reached out to Hillary Frey, with whom I had taken a class at Catapult, and she put me in touch with Andrianna Yeatts at ICM. She is a younger agent, and we quickly became good friends.

When the pandemic hit, I finally had time to work with her on revisions. She sent the manuscript out in June 2020, on what turned out to be the day before the George Floyd murder. So instead of being glued to my inbox, I was out protesting and connecting with friends. Before I knew it, Doubleday got back to us with a preemptive offer.

Having recently read Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings and Michelle Zauner’s Crying in H Mart and now your beautifully immersive story, I’m wondering if we’re seeing a trend.

I am hopeful that the time has come. I have never before seen the [Asian American and Pacific Islander] community this galvanized. It’s almost as if, unfortunately, it had to get this bad for progress to ignite. For the longest time, we were all gaslit into thinking we were model minorities who had nothing to complain about. Now it’s as if we’ve all woken up at once.

I live in daily gratitude for everything I have now that would have been unfathomable for Chinese immigrants not so long ago. Our lives are built on the shoulders of giants. Honoring their legacy means living up to our privilege and continuing to push the movement forward. My vision for the beautiful country is this: to every new generation, more rights, more equality, more justice.

Marion Winik is the author of The Big Book of the Dead and other titles.