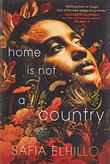

In Home Is Not a Country (Make Me a World, March 2), her first novel in verse, Sudanese American poet Safia Elhillo tells the story of 14-year-old Nima, who is growing up in the U.S. as the Muslim daughter of an immigrant single mom. Her closest friend, Haitham, is both her neighbor and the son of her mother’s best friend. Grappling with poverty, loneliness, unanswered questions about her father, Islamophobia, feeling both too American and not American enough, and a pervasive sense that she is a disappointment to her mother, Nima finds comfort in music and converses with Yasmeen, a sort of shadow twin, the daughter she imagines her mother would have preferred. This expressive jewel of a book with elements of magical realism addresses feelings of dislocation and identity that are both grounded in specific experiences and relatable to any reader who has felt unmoored and adrift. Elhillo spoke with us over Zoom from her home in Oakland, California; the conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you make the transition from poetry to writing a novel in verse?

I was having a conversation with Chris Myers, who runs Make Me a World, and I started gushing about Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red—it exploded so much for me as a poet, it was so strange and expansive—and he was like, You know that’s a novel in verse? One of the stories I tell myself is that I don’t know how to write narrative. Sensation is my primary sense and my primary way of writing and consuming work as a reader. But when I started thinking of this beloved collection of poetry as a novel in verse, it demystified it; actually, it was a form that I’d accidentally been studying this whole time. I think the line from slam [poetry] to narrative is actually pretty straight. Those poems are narrative. You’re building this road for your audience to follow and you have to give them an entry point and then you deposit them somewhere at the end, and it has to have felt like a journey. So again, if you had said narrative to me, I would have gone and hid under the covers, but once I decided to accept this challenge, it turned out that the tools were there the whole time, just by another name.

Speaking of sensation, the book has so many rich sensory descriptors. As I read, I wished I could hear the music that Nima loves so much.

I made a playlist on Spotify to go along with it, because for anyone to read the book without knowing what the songs sound like would feel like a real loss. You don’t have to know what they’re saying—they hold up on their own as beautiful, moving pieces of music. There’s really exciting music coming out of Sudanese communities worldwide. It was almost as fun as writing the book, making the playlist, and I hope people will listen to it.

How did you find poetry in the first place?

There are so many poets in my family—I’m not doing anything original or spicy. My maternal grandfather is a poet [Eltayeb El-Kogali]. My maternal aunt is a poet, playwright, and photographer [Issraa El-Kogali Häggström]. Also, she was the first person I knew who had an MFA, so by the time I was even having that conversation, it was old hat for the whole family. I’m not the rebellious artist. I tried on a lot of hobbies as a kid—there’s a discarded flute, and a violin, and oil paints, and all this stuff probably still in my mom’s basement. With poetry, what stuck wasn’t that there was this magic spark. I grew up in D.C., and there is an amazing poetry community there. Busboys and Poets on 14th and V had an open mic, and a friend invited me to go, and it was like seeing a whole world that I knew I wanted to be part of: If all I have to do to get to keep hanging out with these incredible weirdos is to write a poem? Totally, I will write 10 poems! People have this sort of Emily Dickinson idea of the poet as the hermit, but that has not been my experience; the poetry was almost secondary to the relationships. It’s lonely being an artsy teen. I don’t know that I am a poet without my community. There is the joy of writing a sentence that feels good and accurate, but that’s a secondary joy.

There are so many poets in my family—I’m not doing anything original or spicy. My maternal grandfather is a poet [Eltayeb El-Kogali]. My maternal aunt is a poet, playwright, and photographer [Issraa El-Kogali Häggström]. Also, she was the first person I knew who had an MFA, so by the time I was even having that conversation, it was old hat for the whole family. I’m not the rebellious artist. I tried on a lot of hobbies as a kid—there’s a discarded flute, and a violin, and oil paints, and all this stuff probably still in my mom’s basement. With poetry, what stuck wasn’t that there was this magic spark. I grew up in D.C., and there is an amazing poetry community there. Busboys and Poets on 14th and V had an open mic, and a friend invited me to go, and it was like seeing a whole world that I knew I wanted to be part of: If all I have to do to get to keep hanging out with these incredible weirdos is to write a poem? Totally, I will write 10 poems! People have this sort of Emily Dickinson idea of the poet as the hermit, but that has not been my experience; the poetry was almost secondary to the relationships. It’s lonely being an artsy teen. I don’t know that I am a poet without my community. There is the joy of writing a sentence that feels good and accurate, but that’s a secondary joy.

Why write for teens?

I’ve given adult readers a lot of my time and attention. Anyone can become a lifelong reader at any age, but my particular soft spot is adolescence, because that was my entry point. I’d been a casual reader my whole life; then when I turned 13, it was like a switch was flipped, and all I wanted to do was read. Books were like magic: My own life is mostly boring, sometimes painful, but here are all of these thousands and thousands of other worlds. YA books were so welcoming—just familiar enough in that the character could be having a similar school experience but different enough that I felt like I got to take a break from having to process my own life and just dive in and be in the passenger seat for a little while.

I was fascinated with how you never explicitly name Sudan but include hints about the characters’ cultural origins that readers can pick up on. I knew there were references I was missing that cultural insiders would appreciate—but that did not feel like a barrier to connecting with the heart of the story.

I wanted for there to be little easter eggs for Sudani people to be like, this is definitely Sudan, but I also wanted to give myself permission to imagine a little bit and not feel beholden to having to report on history. I’m obsessed with history, but it is a responsibility. Because it’s a little magical, and there’s jinn, I don’t want anyone to look at this book as a document about Sudan. I wanted to be really mindful [of] writing about a place that I found beautiful, pulling a lot from my own memories of being in Sudan. Sudan is not a country that has historically gotten a lot of incredible PR from the U.S., so I wanted to create a gift and an offering to my community without giving a non-Sudani reader an excuse to have something flat and simplistic to say about Sudan. I don’t want to neaten the immigration story where it’s like, this developing country in Africa is bad, and the glorious, enlightened West is good, and so we came and found a better life here and that is where the story ends. Or we came here and had a hard time and went back home and everything was better because all I needed to do was be in my ancestral homeland. There’s the first stage of diasporic longing, which is that the homeland is this perfect, pristine place, and if I were there everything would be better. And then it sets in that your parents or whoever had a valid reason for wanting to leave, but that’s not to demonize their place of origin.

Laura Simeon is a young readers’ editor.