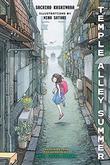

In Temple Alley Summer (Restless Books, July 6) by Sachiko Kashiwaba, translated by Avery Fischer Udagawa, and illustrated by Miho Satake, fifth grader Kazu needs to pick a summer vacation project for school. Two strange things happen: He spots a ghost leaving his house, and when she appears in his classroom, it’s as if everyone else has always known her. Then he sees an old map of his neighborhood that shows a mysterious temple whose name references bringing the dead back to life. Researching this temple becomes Kazu’s summer project, one that leads to friendship with the ghost girl, the unraveling of a family mystery, a hilarious love/hate relationship with a cranky old lady, and a quest to find the ending to an unfinished fantasy story from decades ago. This charming story is both a layered, profound reflection on living life with purpose and a funny, suspenseful book with all the hallmarks of classic middle-grade literature. Kashiwaba, a veteran Japanese author whose 1975 debut inspired Studio Ghibli’s classic animated film Spirited Away, spoke with us over Zoom from her home in Morioka, Japan; Christine Gross-Loh interpreted. Udagawa lives in Nonthaburi, Thailand, and spoke with us separately over Zoom. The conversations have been edited for length and clarity.

Kashiwaba san, how did you become a children’s author?

Sachiko Kashiwaba: I’ve always loved books, and when I entered pharmaceutical school, I knew that as my studies advanced, I wouldn’t have as much time for myself. So in the first two years, I tried to do things I liked. My friends did activities like painting or mountain climbing; I started writing children’s books. Later, as I worked as a pharmacist, I also published here and there, and when my children were born, I started working as a children’s author as my main profession. At first, I wrote purely for my own pleasure—and even after I became a full-time author, I retained that feeling of enjoyment.

This book deals with some serious subjects such as the meaning of life and facing death.

SK: I think the fact that we have both the world we live in and another world out there is what makes for a rich existence, and I always believe that it’s when we strive to expand our own world to include that other one that we can achieve a sort of happiness. Many readers have told me that it made them think more deeply about life and existence, and that’s left me with the impression that there are a great many young people who, through reading my book, were compelled to ponder life more seriously. This book came out [in Japan] the year of the [Tōhoku] earthquake [of 2011]. I happened to publish this book about life and death during a year when many people lost their families and wished for their loved ones to return to them. I hope it reaches readers who have lost loved ones and wish this kind of story could really happen. I’m very excited to be published for the first time in America. Life is precious no matter what country you’re from, what kind of child you are. So it would make me very happy if, even just a little bit, this message comes through for American children who read my book.

that we can achieve a sort of happiness. Many readers have told me that it made them think more deeply about life and existence, and that’s left me with the impression that there are a great many young people who, through reading my book, were compelled to ponder life more seriously. This book came out [in Japan] the year of the [Tōhoku] earthquake [of 2011]. I happened to publish this book about life and death during a year when many people lost their families and wished for their loved ones to return to them. I hope it reaches readers who have lost loved ones and wish this kind of story could really happen. I’m very excited to be published for the first time in America. Life is precious no matter what country you’re from, what kind of child you are. So it would make me very happy if, even just a little bit, this message comes through for American children who read my book.

You have been writing for young people for decades, so you have seen a lot of changes in children’s lives. Has this affected your writing?

SK: I haven’t changed the way I write for young people, though it’s true they certainly have changed over the years. If I compare them to the way young people were when I was their age, the ways they think, live, look at the future—in all these ways they are quite different. Children today rely on visual things that provide immediate gratification; it’s so much easier to play video games. They don’t have as much experience of listening to their parents or grandparents tell stories—folktales and family memories—and the fun of imagining the world someone is telling you about. I hope to create stories that can overcome these obstacles.

Avery, what drew you to translate this book?

Avery Fischer Udagawa: I had the opportunity to translate a short story by Sachiko Kashiwaba for Tomo, an anthology of YA stories that came out a year after 3/11 [the March 11, 2011, Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami], and I really appreciated the work by her that that exposed me to. Temple Alley Summer stood out to me as a page-turner. On rereading, I saw many great themes: friendship, agency, bravery by “average” kids, death as part of life, community.

The novel is deeply embedded in Japanese culture and yet feels universal in so many other ways. How did you balance this as you were translating?

AFU: I’ve learned to look at the goal of each passage—and the overall story—and if explaining a cultural element was going to be necessary to tell the story, then I would try to do so as stealthily as possible so it wouldn’t stop the flow. But if there was [something] that was going to need a lot of explanation and maybe was incidental, then I would drop it or pull the bits out that were important to the story. There were also places where I could add in flavor that evoked the original. For example, in keeping with the book’s subtle humor around zombies, there’s a place where Kazu sleeps soundly that I was able to call the “sleep of the dead,” a phrase not in the Japanese [original]. My husband is Japanese, and our girls are obviously experts in kidspeak, so I did go through the book with them, and it was a little bit like being squeezed in a vise between my husband’s notes about fidelity to the Japanese and the kids’ “Mom, we do not say that!”

Countries where the majority of people speak English are notorious for having so few works in translation.

AFU: What I’ve noticed raising children outside the U.S. is there’s so little mirror literature for them. My kids read largely in English, [and] they’ve read more about life in New York City than in Thailand. I don’t cherish illusions that a global reading diet vanquishes all our prejudices—Japan is a legendary importer of global children’s literature, yet my biracial kids have experienced prejudice there. [But] we plant the seeds in children that we hope will grow, and if we want to humanize young people of other nations for our kids then we need to get stories, plural, from writers in many groups and cultures. Discussions of diversity in U.S. publishing, which are necessary and long overdue, typically refer to U.S. authors writing in English, yet young readers are growing up in an interconnected world that needs them to have a wider view, so I hope we can think big and include translations. Some prominent Japanese books have elements that English-language publishing dislikes—a fair amount of exposition, episodicity, or characters not the age we expect in certain age categories. I hope we can broaden our minds about what books can be and how they can work, because children are very open.

Laura Simeon is a young readers’ editor.