After reading a pair of essays by U.S. District Judge Jed S. Rakoff—“Jailed by Bad Science,” on the unreliability of forensic evidence, and “Our Lying Eyes,” on the frequency of errors in eyewitness identification—I began to wonder about how these investigative techniques, which we usually don’t question, are narrativized in crime fiction. Do authors write as if the techniques are reliable, or are they presented in all their murky complexity? My interest is not just in crime stories set during the present, at a moment when criminal justice reform has become such an urgent topic, but also in crime stories set at the beginning of the 20th century, when common police procedures, such as mug shots, fingerprinting, and keeping crime scenes uncontaminated, were just developing. The question couldn’t be answered as straightforwardly as I thought, however, because it turns out that the development of police methodology goes hand in hand with the development of professional policing—and the latter took place haphazardly. In fact, policing was such an unregulated and by the seat of your pants occupation that any vaguely “scientific” forensic method must have appeared to be a godsend.

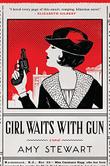

Amy Stewart writes the Kopp Sisters novels, which fictionalize the adventures of real-life Bergen County, New Jersey, Deputy Sheriff Constance Kopp during the first decades of the 20th century. In the first novel, Girl Waits With Gun, a handwriting expert is called in. He turns out to be William Kinsley, who invented the field. “In those days,” Stewart tells me, “the sheriff department and police department were very amateurish. They relied on volunteers…” She describes a scenario in which the police had to go door to door to rustle up volunteers to help catch a criminal; another in which the sheriff arms the three Kopp sisters (none of whom were part of law enforcement at the time) with guns so that they could protect themselves; and notes that it wasn’t until the 1920s that crime scenes were cordoned off, so until then contamination was par for the course. “A hundred years ago,” she says, “there was a lot of frustration about how ad hoc and loosey-goosey law enforcement was. At the time, all the new technology [such as handwriting and fingerprint analyses] was a lifesaver.”

Amy Stewart writes the Kopp Sisters novels, which fictionalize the adventures of real-life Bergen County, New Jersey, Deputy Sheriff Constance Kopp during the first decades of the 20th century. In the first novel, Girl Waits With Gun, a handwriting expert is called in. He turns out to be William Kinsley, who invented the field. “In those days,” Stewart tells me, “the sheriff department and police department were very amateurish. They relied on volunteers…” She describes a scenario in which the police had to go door to door to rustle up volunteers to help catch a criminal; another in which the sheriff arms the three Kopp sisters (none of whom were part of law enforcement at the time) with guns so that they could protect themselves; and notes that it wasn’t until the 1920s that crime scenes were cordoned off, so until then contamination was par for the course. “A hundred years ago,” she says, “there was a lot of frustration about how ad hoc and loosey-goosey law enforcement was. At the time, all the new technology [such as handwriting and fingerprint analyses] was a lifesaver.”

Since a female deputy sheriff was such a rarity, Kopp’s exploits were well documented in local newspapers, and Stewart draws from these accounts to develop her stories. Kopp was responsible for the female section of the jail. Witnesses could be jailed until the trial, Stewart says, and some of the women who were in jail were witnesses to the crimes that men had committed. How crimes were tackled depended on who was tackling them, and the unprofessional nature of the police force is brought to the fore in a telling interaction in Lady Cop Makes Trouble, in which Belle Headison, Paterson, New Jersey’s first policewoman, says to Constance, who makes a $1,000-a-year salary like the other deputies, “The chief expects me to serve out of a sense of duty and honor, and not to take a salary away from a policeman.”

Later, Sheriff Heath tells Constance that her own job may be in jeopardy because her position has no precedent. He says that the sheriff in New York City tried to appoint a woman deputy, “and had to abandon [the scheme] because the law there requires that deputies be eligible voters in the counties in which they serve.” (Women in New York state didn’t have the right to vote at the time.) This illustrates the tangled issues faced in even hiring competent law enforcement officers, let alone codifying evidence gathering techniques.

Nancy Bilyeau, the author of Dreamland, is also deputy editor of the Center on Media, Crime and Justice at John Jay College. Dreamland tells the story of heiress Peggy Battenberg, who spends the summer of 1911 at a luxurious hotel on Coney Island in Brooklyn, New York, where a string of murders takes place. Bilyeau focuses on police harassment and misconduct. “Police were a scary element to anyone who was different, to an immigrant, political person, or a person who wasn’t conforming. They were perceived as a threat,” Bilyeau explains. One example that she found striking in the course of her research, was when thousands of people gathered at Union Square in New York City for a peaceful protest—they wanted an eight-hour workday, with fair and humane work conditions. The police rushed in with clubs to beat them to get them to disperse. Someone protested that it was against the Constitution. “My club is stronger than any Constitution,” a policeman is reported to have said.

When Peggy and her friend, a Serbian artist, go to the police, the Serb immediately becomes a suspect because of his nationality. A policeman tells Peggy, “I am one of the very few Italian police officers on the New York City police force. I accept that I’m under a shadow of doubt every minute to those who believe all Italians are born anarchists, bomb throwers and murderers…”

In the midst of such chaos, when the police themselves were often on the wrong side of the law, and when the law and procedural issues were still being figured out, investigative techniques that promised impartiality and reliability—however much they may be discredited today—must have seemed like a vast improvement on the prevailing state of affairs. Well-researched crime novels dramatize the state of policing in the early decades of the 20th century to great effect.

Mystery correspondent Radha Vatsal is the author of Murder Between the Lines and A Front Page Affair. Sign up for her monthly newsletter here.