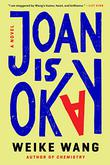

There’s a brilliant alchemy that bubbles beneath the surface of Weike Wang’s novels about the sciences. Her 2018 debut, Chemistry, came infused with a mordant wit that made her tale of a Ph.D. student’s breakdown and recovery “at once moving and amusing, never predictable,” according to our review. The novel went on to rack up acclaim, winning the PEN/Hemingway Award and the Whiting Award.

Now, Wang applies those properties to Joan Is Okay (Random House, Jan. 18), turning her gaze to a Manhattan hospital’s intensive care unit. Joan, her Chinese American protagonist, is an outstanding doctor whose workaholic tendencies draw praise from her boss as well as concern from her hospital’s HR department, which forces her to take a break. Feeling banished at her brother’s home in Connecticut, where her mother is visiting from China, Joan finally has time to ponder what drives her so relentlessly in her career and to confront the realities of her fractured family, now living too close for comfort, just before the Covid-19 pandemic hits.

Joan Is Okay is not being sold as a “pandemic novel”—Covid-19 features nowhere in the jacket copy—but the global health crisis truly turns the screws on Joan, a refreshingly “idiosyncratic character” whom Wang brings to life in a style “so wry and piercing,” our review notes.

Kirkus spoke to Wang via Zoom from her home in New York City. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What was your starting point for this novel?

After Chemistry, where I wrote about a protagonist who is having a hard time with her grad school science program, I was interested in writing a doctor protagonist who is an Asian female. I know so many people like this, and I wanted to create a character who is working in STEM and investigate the model minority stereotype through her. I wanted to have a little fun with that stereotype, not ignoring what someone like her would become through this indoctrination and deindividualization, which is so much of medical training. It has nothing to do with this person being Asian, it’s just that all doctors are trained to become a tool [within a larger system].

Was the pandemic always going to be part of the story?

No. I had finished the draft and turned it in in February 2020 and thought, I’m done. Covid wasn’t in the book at all. I had known about the pandemic since December 2019 because I have family in China, but it just didn’t cross my mind to include it in the book. Then, as my editor was reading the book in March, as things were starting to get bad here, we realized we had to redo the second part of the novel. The more we thought about it, it didn’t make sense for an ICU doctor to not have any awareness of [the Covid-19 crisis]. Otherwise, I would be writing in a vacuum and pretending that this didn’t exist. I knew I had to weave it in. I was reading so much about ICUs in March anyway, so naturally, in the revision process, I incorporated that. I was resistant at first, but I’m really happy I did it.

No. I had finished the draft and turned it in in February 2020 and thought, I’m done. Covid wasn’t in the book at all. I had known about the pandemic since December 2019 because I have family in China, but it just didn’t cross my mind to include it in the book. Then, as my editor was reading the book in March, as things were starting to get bad here, we realized we had to redo the second part of the novel. The more we thought about it, it didn’t make sense for an ICU doctor to not have any awareness of [the Covid-19 crisis]. Otherwise, I would be writing in a vacuum and pretending that this didn’t exist. I knew I had to weave it in. I was reading so much about ICUs in March anyway, so naturally, in the revision process, I incorporated that. I was resistant at first, but I’m really happy I did it.

How did that affect the pacing? Right around the halfway point of the book, it becomes dreadfully clear to the reader that 2020 is coming.

I didn’t want the pandemic to be the story. Joan is working, working, working. I wouldn’t say she’s necessarily scared of the pandemic, because she’s trained for it very well. She starts realizing it’s getting bad [in China], and the headlines progressively get scarier and scarier. It’s occurring to her that a huge wave is coming, and I wanted it to parallel her expulsion from the city because of her hospital’s rules to prevent her overworking. This is the first book that I tried to plot extensively, thinking about outlines. Chemistry is much more internal, and it happens in this nebulous, one-year period in a person’s life. I wrote out an outline mostly of dates because I needed to know the timeline [of the pandemic] really well. In class, I tell my students that a good writer usually has a good control of time. They know when things are going to happen. So I said to myself, in November, in January, what’s going to happen here? The other trick was just trial and error. This story went through so many drafts that I stopped saving them.

So much of what lifts Joan’s voice is her deadpan humor. How did you hone your comedic sense?

Humor is a coping mechanism. Humor keeps the door open for readers to come in. I was in science for most of my 20s, and the stereotype of people like us was that we are robotic or we have no feelings, which is wholly not true. I thought, what if I took that idea and made something a little bit comic to point at the absurdity of that idea? Of course, Joan has feelings. She is not this machine that just goes to work. There’s just a funny way that she thinks about the world. She’s endearing. She has an emotional landscape. But to her co-workers, she’s a complete mystery who does everything right. I wanted to play with that a little bit. She’s so laser-focused in her work, she’s oblivious to what’s around her. In that flatness [of how outsiders perceive Joan], I’m inhabiting this character and giving her roundedness in considering what kind of forces would have made her think, act, and talk like this. Because the book deals with identity and prejudice, which are important to Joan as she moves through the novel, it made sense to have the humor and the absurdity of the plot just hammer home the idea of how model minority can she get?

It’s so common in immigrant narratives to express this idea that being in America automatically leads to a better life. Instead, you have Joan’s parents move back to China after she and her brother are grown. That’s where they can have a better life in retirement. It seems true to what I’m seeing among my friends and their families.

I was trying to challenge this American narrative that life is terrible, but as long as we have each other, it’s going to be OK. I don’t know if that narrative holds water. Sometimes being apart can help the general stability of a family.

Why was it important to show Joan questioning where she belongs?

Joan is a small person. She’s short in stature—“just under five feet tall.” She’s not very vocal. As a doctor, she’s always listening to others in order to assess a situation thoroughly. When other people encroach on her, like her overzealous neighbor trying to welcome himself into her life, she’s so taken aback. When Joan is called back to work [from her brother’s home in Connecticut], the pandemic comes for her. She gets sick, and she has to totally quarantine, and she’s thrilled about it. This is her domain—her apartment, her ICU, which expands to take over the entire hospital [because of Covid-19]. Joan is able to rise to the challenge, and her idea of “home” is expanded. Joan’s story is about reclaiming her space.

Hannah Bae is a Korean American writer, journalist, and illustrator and winner of a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer’s Award.