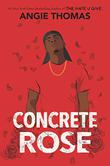

With a phenomenal four years on the bestseller list and a major feature film adaptation, The Hate U Give is a modern YA classic. It’s the story of Starr Carter, a Black teen growing up between the embrace of her home community and the private school where she cannot express her full self—especially after witnessing the police slaying of a childhood friend. Now, with Concrete Rose (Balzer + Bray/HarperCollins, Jan. 12), readers become reacquainted with beloved characters, including Starr’s parents, Maverick and Lisa, when they were teens themselves. Maverick is trying to figure out his relationship to the King Lord gang and how to help his financially struggling mother while balancing an uncertain future against his ambitious girlfriend Lisa’s plans to go to college—and her expectations for him. Finding out that his best friend’s girl Iesha’s baby is actually his? That’s one challenge with huge repercussions that Maverick was not expecting to face. Thomas spoke with Kirkus over Zoom from her home in Jackson, Mississippi; the conversation has been edited for length and clarity. She will be on a virtual book tour this month, discussing the book with noted actors and YA authors including Nic Stone, Jason Reynolds, and Dion Graham.

I have to say that I think this is your best book yet.

You know, it’s the one I love the most as well. I feel like a bad parent saying that, but yeah, definitely my favorite.

Out of all the stories you could have told, why a prequel centering Maverick?

He’s one of the original characters that made his way from a short story I wrote in college to The Hate U Give. I knew so much about him already; past Angie had put down a lot of things to help present Angie. Originally when I wrote The End on The Hate U Give, I thought it literally was the end of me with these characters, but Maverick kept finding his way back, from the kids who are like, “I wish my dad was like Maverick” to the moms coming up behind them going, “I love me some Maverick, I want to marry Maverick.”

A lot of YA fiction keeps parents on the periphery or makes them antagonists. This book bridges that gap.

It’s so easy for us to look at our parents and judge. I think true growth comes when you recognize that your parents are human beings who make mistakes. I started to write Concrete Rose with the idea of what would it be like for Starr or Seven to read this. What kind of view would it give them? What is it like for Seven to see, this is what your dad dealt with, this is why he is the way he is? But for the most part I wanted to look at not these future parents of teenagers but these still teenagers and what they’re dealing with. What’s in Maverick’s head at 17? How is he going to process fatherhood? I wanted to show it’s not easy in hopes that young people will look at the decisions they make and say, you know what? Maybe I’m not ready for that. But [also to] give their parents a little more wiggle room and a little more grace.

It’s so easy for us to look at our parents and judge. I think true growth comes when you recognize that your parents are human beings who make mistakes. I started to write Concrete Rose with the idea of what would it be like for Starr or Seven to read this. What kind of view would it give them? What is it like for Seven to see, this is what your dad dealt with, this is why he is the way he is? But for the most part I wanted to look at not these future parents of teenagers but these still teenagers and what they’re dealing with. What’s in Maverick’s head at 17? How is he going to process fatherhood? I wanted to show it’s not easy in hopes that young people will look at the decisions they make and say, you know what? Maybe I’m not ready for that. But [also to] give their parents a little more wiggle room and a little more grace.

This book gave you the opportunity to complicate and humanize Seven’s mother, Iesha.

I know the real Ieshas: I grew up with some of them, or they had Iesha as a mom and I witnessed how it affected them, but I also got glimpses of how these women came to be who they were. I see Iesha as a little girl being forced to play a grown woman: There’s so much vulnerability in her, but she hides it in such a harsh, brash way. It was important for me to explore this character so we can recognize that she’s a product of her environment and upbringing. Why do we see her in The Hate U Give as so uncaring and cold? In Concrete Rose she abandons her child; well, let’s look into the why. She was one of my favorites to write.

I understand that the writing of Mildred D. Taylor had a profound influence on you.

Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry was the book for me coming up: I’m a Black girl in Mississippi, here’s a book about a Black girl in Mississippi, written by a Black woman from Mississippi. It gave me the mirror I needed. I love the Logan family and the way they loved one another, the way they stood by one another. They struggled a lot, but they had each other, and I wanted the Carter family to be a modern take on that, to have that same love and affection and foundation for Starr as Cassie [Logan] gets. I was reading the book to refresh my brain and [there’s] a line where Cassie describes her mom as being “a disrupting maverick.” I was like, huh, that’s what Starr’s dad is. Why not name him Maverick? Maverick is a lot like Cassie’s mom: a force in the community who’s standing up for what he believes in.

What feedback have you received from teens that has had the biggest impact or been most surprising?

The best messages are from teen readers who reach out and say, “I hate reading but I read your stuff in a day.” I have to tell them, you don’t hate reading, you hate what you’ve been forced to read. There’s no such thing as a reluctant reader; there are unimpressed readers. The messages that really get to me are the kids who are like, “I decided to speak out because of Starr or Bri [from On the Come Up]. I was not happy with an issue in my community and I’m going to do something about it. Your book empowered me.” That’s an honor and a blessing.

The ones that surprise me the most are the kids who come from worlds completely unlike those girls’ and yet still they have connected with the books. I’ve heard from kids in rural Texas who live in towns that are completely White, whose parents have trucks with Confederate flags on them, and they’re like, “I get why people say Black Lives Matter now.” Or “I’ve read your book, and I’m gonna do my best to be anti-racist.” I’ve had to check myself on the assumptions I make about them. I’m grateful that they’re making me change and evolve by [their] learning and growing from my work.

Do you feel as if Concrete Rose is arriving in a different publishing climate than The Hate U Give?

Would I have been as afraid to write Concrete Rose as I was to write The Hate U Give? I would have been more afraid. I wouldn’t have been bold enough to write it and wouldn’t have thought that YA publishing would be accepting of not just a Black boy and teen pregnancy—because we’ve seen that before in The First Part Last by Angela Johnson, which is a phenomenal book that gave me permission to write Concrete Rose—but also gangs and stuff like that. Are we where we should be? No. We have a whole lot more work to do, but I’m thankful for where we are. I hope that we don’t settle, because young people need as many mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors—in the words of Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop—as they can get, and we owe it to them to provide a multitude.

Laura Simeon is a young readers’ editor.