A tiny, impoverished order of nuns in a remote corner of Brooklyn has been praying for world peace continuously for 347 years. Now, to keep the lights on and the vigil going, the elderly sisters of Our Lady of the Highway start brewing beer and bring in a rather unusual new Mother Superior as well as some undocumented recruits from Central America. They are also joined by a beautiful insurance adjuster named Lola who has magical powers, is a saint, or possibly is just plain nuts. Meanwhile, their cloister has been targeted for acquisition by the evil CEO of Magnificent Waste Management, Inc., who already owns the rest of the neighborhood.

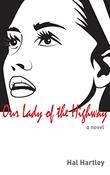

Cinematic? Indeed. This is Our Lady of the Highway (Elboro Press, June 14), the debut novel of acclaimed independent filmmaker Hal Hartley (The Unbelievable Truth, Trust, Henry Fool, etc.), known for his work with such actors as Adrienne Shelly, Edie Falco, James Urbaniak, and Martin Donovan. Hartley discussed his pivot to fiction recently on Zoom; our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What was the original inspiration that started you working on the book?

It was something about nuns making beer. I’m always interested in the way genuine religious belief bangs into the secular world and the conventions of everyday life.

Why was this project a novel rather than a screenplay?

Actually, it did begin as a script for a TV series. It was the first time in my career where I had to pitch—go into studios and tell them the story, explain why the show would be exciting. This required a lot of talking around the dialogue I had written, fleshing out the characters and their backgrounds, extrapolating from what was there on the page. If I’ve learned anything in my years of screenwriting, it’s that the only thing you put in a script is a description of the activity and the dialogue: what people say and what they do. You want the audience to infer about their motivations and feelings.

Actually, it did begin as a script for a TV series. It was the first time in my career where I had to pitch—go into studios and tell them the story, explain why the show would be exciting. This required a lot of talking around the dialogue I had written, fleshing out the characters and their backgrounds, extrapolating from what was there on the page. If I’ve learned anything in my years of screenwriting, it’s that the only thing you put in a script is a description of the activity and the dialogue: what people say and what they do. You want the audience to infer about their motivations and feelings.

And the actors, too, I would imagine?

Actually, a large part of my approach to directing is to remind the actors not to psychologize too much in their performances.

But in a novel...

Right, in a novel, you’re expected to get into the heads of the characters. I’ve always loved the way a fiction writer can slip into the moment-by-moment consciousness of each character and keep the story moving along. When I got back from Los Angeles, I took the 10 episodes I’d written and turned them into 10 chapters.

This could explain the ending of the book, which seems more like a season finale than the end of the story. Are you planning a sequel?

Yes, I chose to keep the ending as in the script—because series do often end that way, with an opening for a second season, but also because it is something I do in a lot of my films: an inevitable conclusion that doesn’t necessarily resolve. I, too, want to see how this story ends, so I’m planning a sequel. Prose fiction is becoming my main creative work.

Did you seek a traditional publisher for the novel?

I never really thought about going the traditional route. In 2019, I started a publishing company, Elboro Press, because I wanted to make my screenplays available to the like-minded. Then I discovered that I liked making books and ended up publishing the work of other people. When I finished Our Lady of the Highway, it just seemed like the way to go. Actually, it’s the same approach I took with my films—which I guess you could say are self-published.

There’s a lot of Catholic prayer in the book. What was the inspiration for that?

I’m pretty steeped in various kinds of religious thinking and poetry, whether it’s Hebrew, Islam, or Christian. When my father died at 90 and I cleaned out his house, I found materials he had from when he was a young man in the Holy Name Society, which was an evening training program for working-class dads, trying to make them just a little bit more Catholic so they could bring their kids up correctly. There were all these prayer books I had never seen! I literally cut and pasted from those books into the novel.

What books published this year were among your favorites?

I’m afraid I’ve spent the entire year in the past—my summer reading project was the collected stories of Clarice Lispector. Reading Clarice was a project, a relationship—fueled by a sense of something kind of miraculous being done to the space and time around me as I read. I hear and see and feel more acutely even as I have to set her book aside for a while and take a walk.

Marion Winik is the host of the NPR podcast The Weekly Reader.