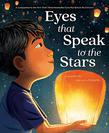

Bestselling picture-book author Joanna Ho is back with the follow-up to her lauded debut, Eyes That Kiss in the Corners (2021). With Eyes That Speak to the Stars (Harper, Feb. 15), Ho continues with her trademark “poetic celebration of body diversity, family, and Chinese culture,” as our review puts it. Ho spoke with us via Zoom from her office in the San Francisco Bay Area, where she works as a high school vice principal. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What inspired you to write a follow-up to Eyes That Kiss in the Corners?

My editor introduced the idea. I had some hesitancy because I don’t want to gender books intentionally. I really struggle when people say “girl books” and “boy books.” What about nonbinary people? I hope that people can find universality in all books. But after thinking about it, I realized that my son would love to have a book where he can see himself, too. If there was an opportunity to increase representation in books, why would I push it away? I thought about Asian boys, Asian men, and the stereotypes that have been so dominant and paint such a limited and inaccurate picture of who we all are. I hope that young boys and men—fathers, uncles, grandparents—can see themselves in the story, too.

Eyes That Speak to the Stars starts out with a painful incident at school for your young boy protagonist, in which a friend draws an offensive picture depicting him with slits for eyes. Why did you choose to open there?

Being bullied and made fun of is a journey that many of us experience, so I tried to put it in the first book, and it didn’t work. In this second book, I wanted to be clear that this happens and has a deep impact. There’s this fine line of “Maybe [the friend] didn’t mean it. Maybe it wasn’t supposed to be hurtful.” I hope [the book] can open up conversation for young people, with families and at schools, about why this kind of microaggression is hurtful and racist and how we can talk about it and prevent it in the future.

Who do you picture as your ideal reader?

I am writing because I am hoping that young Asian children see themselves in stories. On one level, it’s been life-changing to realize the thirst that the Asian community has for stories that represent us. Eyes That Kiss in the Corners changed me as an educator and as a human. Earlier on as a writer, I would have said, “I hope everyone can see themselves in my stories.” I do hope that, and I also hope that people like me, who never saw themselves [in stories] while growing up, that we see ourselves in these stories. There’s a third Eyes book that’s coming out about adoptees. Though I’m not an adoptee, I hope that resonates truthfully. [Another book in progress,] Say My Name is about the beauty of our names and saying them correctly. That one isn’t specific to only Asian readers, [and] I hope it speaks to a lot of people. I believe picture books are meant for everyone, including high school kids, college kids, parents, and teachers.

I am writing because I am hoping that young Asian children see themselves in stories. On one level, it’s been life-changing to realize the thirst that the Asian community has for stories that represent us. Eyes That Kiss in the Corners changed me as an educator and as a human. Earlier on as a writer, I would have said, “I hope everyone can see themselves in my stories.” I do hope that, and I also hope that people like me, who never saw themselves [in stories] while growing up, that we see ourselves in these stories. There’s a third Eyes book that’s coming out about adoptees. Though I’m not an adoptee, I hope that resonates truthfully. [Another book in progress,] Say My Name is about the beauty of our names and saying them correctly. That one isn’t specific to only Asian readers, [and] I hope it speaks to a lot of people. I believe picture books are meant for everyone, including high school kids, college kids, parents, and teachers.

So now, with three picture books down (including 2021’s Playing at the Border: A Story of Yo-Yo Ma), what do you hear from your readers, both children and adults?

My three favorite things that I’ll hear as a pattern are that, first, young children or adults refer to their own eyes as “eyes that kiss in the corners.” I just love that, to think that we can change the vocabulary. We’re not “slit-eyed”; our eyes aren’t “slanted” or “almond-shaped.” I also hear from adults who tell me that they bought [the previous Eyes book] for their kids, who said, “That’s you, Mommy. That’s me, Mommy.” They literally see themselves in the book. I’ll also get some version of, “I don’t even have kids but I bought it for myself and all my sisters and my mom, and we all cried when we read it. I wish I had this when I was a kid.”

Speaking of word choice, how do you find such precision in your writing?

I’m always thinking backward from What is my ultimate goal? and planning from there. I knew I wanted to follow a theme of looking up and how our eyes tilt up and playing with language. For the theme of the book, I didn’t want to gender [the message] and say that boys are powerful and girls are beautiful. That’s not the message. In the first book, I hope that the power message comes through, and in the second, I was going back and forth with my editor wondering if I should just say “boys should be beautiful, too.” Ultimately, it was this idea that we are powerful, we are visionary, we can see a future that we can change to make it better than the past.

Hannah Bae is a Korean American writer, journalist, and illustrator and winner of a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer’s Award.