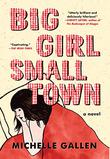

Majella O’Neill is an unlikely fictional heroine. The protagonist of Michelle Gallen’s Big Girl, Small Town (Algonquin, Dec. 1) is, as the title makes plain, a heavyset young woman in a little Northern Irish town not long after the 1994 cease-fire. She’s a compulsive list-maker, obsessive watcher of Dallas videotapes, and employee at A Salt n Battered, a fish-and-chips shop—or “chipper,” in the local parlance. Her father has disappeared—a connection to the Troubles is hinted at—and her needy mother drinks too much and expects her daughter to wait upon her. Majella is probably autistic—“sometimes [she] thought that she should condense her whole list of things she wasn’t keen on into a single item: Other People”—but she’s absolutely winning, and readers will warm to this offbeat, thoroughly realized character. Big Girl, Small Town is Gallen’s debut, and it’s already been nominated for book awards in Ireland and the U.K. and is currently being adapted for television. Gallen, 45, recently joined me on Zoom from her home in Dublin to discuss the novel’s long gestation; our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What was the genesis of Big Girl, Small Town?

I started writing it, I think in 2006. I’d written a short story that year for The Stinging Fly, which is a really great journal here in Ireland. I couldn’t let go of the atmosphere in the story—it was [set] in a chipper, it featured a disgruntled employee who was a man, it had the alcoholic mom, it had the missing dad, it had all that unhappiness, and fish and chips, and sizzling fryers. I really wanted to make the story bigger. I was working for the BBC at the time as a freelancer, so I just took a month off—it was November, and I did NaNoWriMo [National Novel Writing Month]. I wrote 70,000 words in a month.

Had you ever tried to write a novel before?

No, I didn’t tackle the novel. I’d been writing for years at this point, but when I was 23, I was living and working in London, and I contracted autoimmune encephalitis. I went from starting off my career, having this really exciting life in London, to being shipped home in a wheelchair to my parents because my brain had swollen up and crushed itself. I went from not knowing what my second name was to having to learn how to make a cup of tea—all these really basic things that you might not imagine you’d ever have to learn twice. As a part of my recovery, I kept a diary, because my memory was so shot that I literally couldn’t remember if I had breakfast or not. From this point of really struggling to even write a word or write my own name down to being able to write a novel was quite a trip for me.

No, I didn’t tackle the novel. I’d been writing for years at this point, but when I was 23, I was living and working in London, and I contracted autoimmune encephalitis. I went from starting off my career, having this really exciting life in London, to being shipped home in a wheelchair to my parents because my brain had swollen up and crushed itself. I went from not knowing what my second name was to having to learn how to make a cup of tea—all these really basic things that you might not imagine you’d ever have to learn twice. As a part of my recovery, I kept a diary, because my memory was so shot that I literally couldn’t remember if I had breakfast or not. From this point of really struggling to even write a word or write my own name down to being able to write a novel was quite a trip for me.

That’s extraordinary.

There was a full year where I needed my family to care for me. The year after that I moved to Dublin—well, there was an aborted attempt to move back to London that was just really off the cards. I moved to Dublin, and after about a year there I stepped back into what I think of as a proper job. And I was writing all the time in the background. There was always a furious battle to make sure I was able to earn money and to do my job and to keep my flat. And also to write—it was all quite hard work. And when you have a brain injury, there’s a before and there’s an after, and I have to work in very different ways now to make my life work, to make my writing work.

What was it like trying to sell the novel?

I had like no interest in Ireland. This was at a point where people were like, The Troubles are over, we’re done with that. I had a lot more interest in London—at least I was having conversations, and people were telling me how much they enjoyed the book. But they were finding Majella quite a difficult protagonist. I had the most interest in New York, but again, I kept being asked this question, What’s wrong with Majella? I knew she was kind of unusual.

The turning point in getting the novel published, for me, was when one of my relatives got a relatively late diagnosis of autism. It came late in comparison to the men or the boys in our family who tend to get diagnosed early—they’re classic presentations. I decided to read up a bit more on the female presentation of autism, and when I started even the most basic reading of it, I was like, Oh my God. OK. I realized that I created a portrait of an autistic woman, because these types of behaviors were incredibly familiar to me. What’s wrong with Majella? There’s nothing wrong with Majella. She’s an undiagnosed autistic woman. And she’s fascinating.

The book never makes explicit that she is autistic. And we never learn exactly why Majella’s dad has disappeared—though we understand it is connected to the Troubles.

When I was growing up, we told a lot of stories. And we were really good with these set pieces—a big, complicated, funny story, and we’d all know it. And then there’s this other level of story—a kind of half story where you would never actually learn the right or the wrongs of it, or where the person had ended up, or why the thing had happened. There’s a culture of silence in Northern Ireland. The IRA used to say, Whatever you say, say nothing. I know when the book was coming out, I felt very anxious because I thought, Are people going to think that I’ve said things too clearly? My generation was trained not to speak quite so clearly about things that happened. We still don’t.

Despite all this, it’s a wonderfully funny book. It was nominated for a comedy prize in the U.K.

Yes! The Comedy Women in Print Prize. Helen Lederer, who’s an absolute comedic genius [best known to American audiences from her role on Absolutely Fabulous], set it up because she was quite tired of the men getting nominated always for the prizes set up for for your funnymen. I got longlisted and then shortlisted. Where I come from everybody tries to be funny—even in the darkest moments, somebody would say something really, really hilarious. It’s a marvelous coping mechanism. I’m all for dark humor and trying to find the funny angle on even the worst situations. I grew up with incredibly funny people. I wanted to capture that in the book.

One of the things you really capture also is the way the Northern Irish speak—the cadences, the slang. Is there an audiobook?

There is an audiobook, and it’s Nicola Coughlan. I don't know if you’ve watched [the TV show] Derry Girls yet? Nicola Coughlan’s one of the Derry Girls, and her first ever audiobook was Big Girl, Small Town. She does a brilliant job. And one of the things I do feel is that Nicola gives you permission to laugh. Nicola really brings out the comedy, she just absolutely knows how to do the accent. I mean, she does the grief, but she really brings out the laughs as well.

Tom Beer is the editor-in-chief.