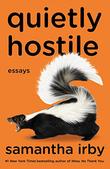

Samantha Irby knows her shit—figuratively and, as fans of her bitches gotta eat! blog and four collections of personal essays know, quite literally. Her carnal knowledge—sexual but especially scatological, thanks to Crohn’s disease—is vast. Her grasp of American poverty, earned.

In her latest collection, Quietly Hostile (Vintage, May 16), Irby offers her version of bathroom etiquette but also shares a wrenching scene of her and a sister at their mother’s deathbed. In the extended and episodic “Superfan!!!!!!!” she riffs on Sex and the City; Irby was hired to write for the reboot of HBO’s iconic series. For a self-described queer, Black, fat girl who lives in rural Michigan with wife Kirsten Jennings and two stepchildren, penning lines for Carrie Bradshaw and Co. has been a little mind-blowing.

In Irby’s able hands, the embarrassing can be harrowing and hilarious, but it seldom takes on the patina of shame. We recently spoke about Quietly Hostile on Zoom; earlier in the week, she’d been recording the audiobook. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

So how did the recording go?

You know, I write a lot of very long, circuitous sentences that are funny in print, but when it comes to recording, they’re not. So, I’m always figuring out where to breathe in real time and how to make it sound like I’m effortlessly telling a story. I should rehearse, is basically what I’m trying to say.

There’s a deep generosity to how you share the body-awareness stuff, the illness-awareness stuff. It must be freeing for your readers.

When I first got diagnosed with Crohn’s, I had never even heard of it before, let alone known people who have it. And it’s one of those diseases that is embarrassing—at least my version of it has been more embarrassing than life-altering in the bad way. Writing about it at first for me was just amusing. It’s like, I’ve got to turn this into something funny or I will just cry and feel like I’m the only person on Earth who’s wearing a diaper. But then when my first book came out, I did a bookstore event in Milwaukee, and one of the people brought me a roll of fancy toilet paper. And she was like, “OK, this is a joke, but I just want to tell you I have irritable bowel disease, and it’s just nice for someone to be writing about it.”

When I first got diagnosed with Crohn’s, I had never even heard of it before, let alone known people who have it. And it’s one of those diseases that is embarrassing—at least my version of it has been more embarrassing than life-altering in the bad way. Writing about it at first for me was just amusing. It’s like, I’ve got to turn this into something funny or I will just cry and feel like I’m the only person on Earth who’s wearing a diaper. But then when my first book came out, I did a bookstore event in Milwaukee, and one of the people brought me a roll of fancy toilet paper. And she was like, “OK, this is a joke, but I just want to tell you I have irritable bowel disease, and it’s just nice for someone to be writing about it.”

How do you modulate your vulnerability?

There’s one part in this book where I finally admit, I think for the first time in one of my books, how—what is the word? It’s not bad—how self-conscious I am about having never finished college. I often talk about people coming home from college when I was a teenager or being in a situation where everyone knows the right words to say, and I’m like, Ha, here are some jokes. So, it took me a minute to say that and admit it and put that out in the world. But the only time I really think about the vulnerability is if I’m writing something sad; I try not to write anything that would make me cry if you asked me about it.

You have a way of distinguishing between embarrassment and shame. They’re not the same thing, right?

Right. Embarrassment, I think, is more about the people who may be seeing you. It would be awkward for me to explain to this woman waiting outside the single-stall bathroom, the one who thinks I passed a dead body in the 15 minutes I’ve been in here. That’s embarrassment. Shame is, I’m terrible and should never leave the house because this thing is going on inside me. I can eventually spin embarrassment into a funny anecdote. To go down the shame spiral of Yeah, of course I’m bad, and it’s unfixable, and this is going to be who I am—resisting that is like an everyday practice for me.

Is it a little “pinch me, I must be dreaming” to have loved Sex and the City and now work on And Just Like That…?

I thought it was bullshit when my agent told me, “[Executive producer] Michael Patrick King would like to talk to you.” I was like, f- you. What day is it? April Fools’? I feel like the only way I got through it—especially the first season—was because we were remote. If I had been in a fancy conference room with posters of Carrie Bradshaw on the wall, I would have felt very intimidated. But because I was just sitting in the corner of my living room on my same laptop, it took some of the pressure off.

Was the pressure a surprise?

It caught me off guard, like, how big the show was and how many people had opinions. The thing about the opinions is, I don’t get mad. But my response to them was, Oh, wait, you misunderstood. Let me tell you what I was trying to do. And you can’t do that.

OK, so the “Shit Happens” chapter reads like the new rules of grown-ass etiquette. It’s so charming.

I’m so glad, because it’s one of those things that my editor will never say, “It’s too much.” But it does feel like a coup every time I’m trying to do something disgusting and they’re like, OK. For real? I can have a pee chapter and a poop chapter?

You utilize lists a lot.

What am I writing, a term paper? We need a commercial break.

Do you laugh when writing?

Yes, I’ll just be chuckling, and my wife will be thinking I’m looking at a meme or something. She’ll ask, “What’s funny?” And I’m like, “I just wrote this sentence.” What an asshole, right? The one kind of sad thing about audiobooks (because they discourage it) is when I perform my work, I always laugh because sometimes people don’t quite know when to laugh. Especially when you’re revealing a lot. She said her body looks like a bag full of tennis balls. Do you get to laugh? I have to help them.

You tend to have little existential asides through the book, like “but since we live in hell….” How bad is this mortal coil?

I think that urge in me comes from wanting to push back against…I don’t know what to call it other than a sort of toxic positivity. And I don’t think all positivity is toxic, OK? A thing I hate is the kind of unrealistic platitudes we get from people, like, “buck up,” “be happy,” and “I did this. You can do it.” I’m not going to tell you exactly how I did it, but I’m going to tell you that you, too, can have this beautiful life that you see on my Instagram. I don’t ever want to connect to someone in a phony way, even if it is humiliating. We live in rural southwest Michigan. There’s no money [here]. The number of kids my wife has to refer to the teen homeless shelter—the fact that there’s a need for a teen homeless shelter, it’s like, I can’t ignore that. I also can’t get bogged down in it. So, I kind of view what I do as like, listen, we’re all in a landfill. Let’s make fun of that garbage pile over there. It’s connection through commiseration. And I think that’s part of what people appreciate. Even when I’m funny and telling a good story, I never get too far away from, well, remember, life is awful—right? And we’re all going to burn up.

Lisa Kennedy writes for the New York Times, Variety, the Denver Post, and other publications.