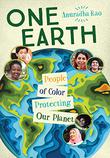

In January, at the World Economic Forum annual meeting in Switzerland, the Associated Press cropped Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate out of a photograph that featured white environmentalists Greta Thunberg, Luisa Neubauer, Isabelle Axelsson, and Loukina Tille. Anuradha Rao’s debut book, One Earth: People of Color Protecting Our Planet (Orca, April 7), isn’t intended as a response to this exclusion, but it feels like one. One Earth addresses a movement that has historically focused on the work of white people by shining a light on 20 black, Indigenous, and other “environmental defenders” of color from around the world who are spearheading innovative programs to preserve the environment. This book for young readers includes Ismail Ebrahim, who researches and saves rare and endangered wildflowers from extinction in South Africa; Ken Wu, who works to protect old-growth forests in British Columbia; and Richelle Kahui-McConnel, who filters toxins out of waters in New Zealand.

Environmentalism is an extension of Rao’s genealogy. A few thousand years ago, her ancestors lived in northern India along the banks of the Saraswati River. When it dried up, they became environmental refugees and migrated south to Goa. Her parents emigrated from southern India to Canada, where Rao was born. Rao’s Hindu culture and family history have shaped her perspective as a conservation biologist and researcher.

She talked about One Earth from her home in Vancouver, the unceded territory of the Coast Salish people.

What led you to write this book?

I have been working in the environmental field more than 20 years. At events, I’m oftentimes the only brown person in the room. I’m also one of the only people in my cultural community to have gone into this line of work. It doesn’t have to be this way. So I wanted to celebrate diverse role models in the environmental movement in a book for young people.

What is an “environmental defender”? How is this different from an activist?

Words are tricky. Activist and environmentalist can be loaded words (all words are), so I was trying to find a term that was as neutral and inclusive as possible. In the conversations I had with people, especially Indigenous people, “environmental defender” seemed to be OK.

Can you talk a little about the whitewashing of the environmental movement?

This movement has whitewashed those who are on the front lines. I could have written an entire book about Indigenous defenders. I could have even written an entire book about Indigenous defenders only in British Columbia, where I live. So many people are in a life-and-death struggle trying to preserve their cultures and traditions. And it’s so important for young people of color who are trying to find something to do about environmental issues to see people who look like them. I explicitly addressed this in the book when I asked the defenders how their culture helps them to achieve success in a way that the mainstream white environmental movement hasn’t.

Why is it important to center the environmental work of Indigenous people?

There’s this understanding that conservation is for white people and that the people who are the stewards of the land and the waters need to be educated about conservation instead of the other way around. The defenders in the book all said this. Environmentalism is a very colonial discipline.

There’s this understanding that conservation is for white people and that the people who are the stewards of the land and the waters need to be educated about conservation instead of the other way around. The defenders in the book all said this. Environmentalism is a very colonial discipline.

Identity becomes very important. Indigenous people have a deep understanding of the world around them, how to interact with it, how to respect and sustain families for generations to come. It’s not someone else’s job to tell them how to do this.

Is there an overall theme that’s common throughout these profiles?

Many of the interviewees suggested that people get out in nature. Go outside and play to see how much you can learn about what’s around you. Walk or ride your bike. Step outside and listen. Learn about native and invasive plants, find out what Indigenous territory you live on. Have a conversation with your family about plastic water bottles. Find out something you’re really passionate about and go for it. Start these conversations at home with friends and members of your community. Even an interest in exploring nature can grow into bigger things.

Anjali Enjeti is an Atlanta-based journalist whose reviews regularly appear in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.