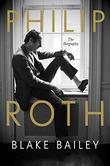

Editor’s Note: This interview with Blake Bailey, author of Philip Roth: The Biography, took place on Feb. 26 and ran in the April 1 issue of Kirkus Reviews. Not long after the book was published on April 6, Bailey was accused of sexual assault, and of grooming students while a teacher at Lusher Middle School in New Orleans in the 1990s. On April 28, publisher W.W. Norton and Company announced that it would take the Roth biography (and another book by Bailey) out of print.

Whether or not you’ve read a word of the 31 books produced by Philip Roth (1933-2018), you are doubtless aware of his reputation. While his 1959 debut, Goodbye, Columbus, got his career off to a flying start—it won a National Book Award—it was Roth’s fourth book that made the impression that would follow him the rest of his days.

After Portnoy’s Complaint appeared in 1969, the public believed Roth was Portnoy—an oversexed “self-hating Jew” whose attitudes were so provocative that some claimed he might incite a second Holocaust. Neither the protestations of Roth and his many admirers nor his distinguished body of work ever managed to alleviate the problem; some books, such as his second National Book Award winner, Sabbath’s Theater (1995), only dug him in deeper.

“It was certainly a reference point for the Swedish Academy,” says biographer Blake Bailey, in reference to his subject’s perennially dashed Nobel Prize hopes. (Roth managed to be philosophical about it; when the prize went to Bob Dylan in 2016, he commented, “It’s okay, but I hope next year they give it to Peter, Paul and Mary.”)

Blake Bailey. Photo by Nancy CramptonIn 2012, after a lengthy vetting process, Roth selected Bailey, known for his lives of John Cheever, Richard Yates, and Charles Jackson, as his official biographer. Bailey took over from Roth’s longtime friend Ross Miller, who had completed only 11 interviews in almost as many years; Bailey did nearly 150 more and transcribed dozens by others. He reviewed the materials in 200 boxes archived at the Library of Congress and spent hundreds of hours with Roth himself. The result is Philip Roth: The Biography (W.W. Norton, April 6), an exceptionally lively 800-page book that presents a man who, at his best, was “one of the most honorable, generous, sweet, vulnerable, funny people you would ever like to meet,” Bailey says.

Blake Bailey. Photo by Nancy CramptonIn 2012, after a lengthy vetting process, Roth selected Bailey, known for his lives of John Cheever, Richard Yates, and Charles Jackson, as his official biographer. Bailey took over from Roth’s longtime friend Ross Miller, who had completed only 11 interviews in almost as many years; Bailey did nearly 150 more and transcribed dozens by others. He reviewed the materials in 200 boxes archived at the Library of Congress and spent hundreds of hours with Roth himself. The result is Philip Roth: The Biography (W.W. Norton, April 6), an exceptionally lively 800-page book that presents a man who, at his best, was “one of the most honorable, generous, sweet, vulnerable, funny people you would ever like to meet,” Bailey says.

Yet, argues the author, “I did not sugarcoat,” honestly portraying Roth as a Lothario “without a monogamous bone in his body.” The book carefully reviews the charges of stinginess, misogyny, and cruelty leveled by his second wife, actress Claire Bloom, in her 1996 memoir, Leaving a Doll’s House, and makes note of its various omissions and distortions.

We explored several aspects of the biography with the author over Zoom from his home in Portsmouth, Virginia. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you—“a gentile from Oklahoma,” as Roth called you in your job interview—manage to become biographer of the favorite son of Newark, New Jersey’s almost-all-Jewish Weequahic High?

From the beginning, I made a conscious decision not to be intimidated by him, and indeed, when Philip was at his most imperious I tried to be at my most humorous and unflappable. It’s very easy, actually, to pierce Philip’s veneer of imperiousness, because his sense of humor is never far from the surface, whatever his mood.

We learn that Roth was always mystified and irritated by charges of misogyny. As far as he could see, he loved women and had always had women in his life as mentors, friends, lovers, and colleagues.

While he was never faithful to anyone, ever, the majority of Philip’s girlfriends had a very good opinion of him—that cannot be emphasized enough. He kept in touch with them, and while he very frequently gave money to anyone in distress, with his old girlfriends he was particularly generous.

But for many of his female fans the problem wasn’t his behavior in real life, it was the depiction of female characters in his books. You quote his friend the biographer Hermione Lee as saying Roth had four types: “overprotective mothers,” “monstrously unmanning wives,” “consoling, tender, sensible girlfriends,” and “recklessly libidinous sexual objects.”

I do think Hermione is basically correct, yet I also think Philip was capable of nuanced female characters when it served his purpose. Brenda Patimkin from Goodbye, Columbus—Brenda is very bright and spunky and admirable. Maria Freshfield, Zuckerman’s lover in The Counterlife; Martha Reganhart, from Letting Go; and Drenka, of course, from Sabbath’s Theater—she is just as shamelessly lascivious, and as funny about it, as any reprobate male.

Your book connects these characters to their real-life inspirations. It was fascinating to see how people and experiences turned up in Roth’s work in fully fictionalized contexts.

Usually they turn up in somewhat transmuted forms. Claire Bloom was suspicious about the “real-life” identity of Maria Freshfield, who’s so vividly evoked, and indeed she was mostly based on one of Roth’s secret lovers at the time. Nonetheless, he could plausibly tell her that Maria was actually based on a different, pre-Bloom lover, Janet Hobhouse, who also had a posh accent.

Roth had many close male friendships, though these were almost always marred by misunderstandings and quarrels eventually. Bellow, Updike, and Kundera, along with many less-well-known names, as well as his previous biographer, Ross Miller...it almost seems like he never had a friend he didn’t fall out with, at least temporarily.

Well, but often these falling-outs were largely the other person’s fault, and Philip didn’t see them coming because he had a lot of blind spots where other people—especially friends—were concerned. Philip cultivated his wisdom in his art, not so much in his life. He didn’t always see people very clearly, and that is more common than you may think among writers of the first rank. Cheever was very much the same way, Yates was very much the same way; they spend so much time burrowing inside themselves that they stopped looking at what’s in front of their noses.

Well, but often these falling-outs were largely the other person’s fault, and Philip didn’t see them coming because he had a lot of blind spots where other people—especially friends—were concerned. Philip cultivated his wisdom in his art, not so much in his life. He didn’t always see people very clearly, and that is more common than you may think among writers of the first rank. Cheever was very much the same way, Yates was very much the same way; they spend so much time burrowing inside themselves that they stopped looking at what’s in front of their noses.

The only time I ever saw Roth in person, on tour for his memoir, Patrimony, someone asked him, “During your long career there have been dramatic changes in mores and culture. How do you think this has affected your work?” And he said, “Well, I think it’s my work that has affected the change in mores and culture.”

[Laughs.] That was not an idle claim. Singlehandedly, Portnoy abolished the obscenity laws in Australia. Here in the U.S., the New York Times—whose reviewers otherwise applauded the novel—ran a very deploring editorial titled “Beyond the (Garbage) Pale.” Philip also said that in a free, democratic society, the culture is a maw, and he’d had about as much effect on it as he would had he become a lawyer, as he’d originally planned.

Roth’s directive to you, quoted in the book’s epigraph, was to make him interesting. You certainly accomplished that. Do you think he would like the book?

Philip and I developed a rapport. I knew when he would like something, and I definitely knew when he wouldn’t—when he would find it psychobabble or otherwise reductive or kitschy. I got a pretty well-developed antenna for this over time. But insofar as Philip had an artistic manifesto, it was to let the repellent in, bad and good. Show who we really are. There are people who have very settled ideas about who Philip was, and they often tend to be negative. It’s quite possible that these people will read my book and still have a disparaging view. But if you read with an open mind, I think Philip comes across as a flawed human being, certainly, but mostly quite lovable.

Marion Winik is the author of The Big Book of the Dead.