When she finished writing her second novel, Little Fires Everywhere—which became a bestseller and was adapted for a limited series on Hulu—Celeste Ng thought she was going to write a finely observed family drama about a mother and son. Then came the seismic political shift of the 2016 presidential election. “There was the rise of the far right, all the things that had been simmering all along but were really coming up to the surface,” she explains in a recent Zoom interview from her home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “It started to feel almost disingenuous to write a story that pretended all these things were not in the world.”

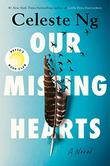

The book she wound up writing is Our Missing Hearts (Penguin Press, Oct. 4), which showcases Ng’s signature storytelling abilities and engaging characters but is set in an unexpected dystopic world. In the wake of a crushing economic and political crisis, the government has passed a law called PACT—the Preserving American Culture and Traditions Act—and political dissent is squashed. Anti-Asian violence is rampant. Ng’s protagonist, 12-year-old biracial Bird, lives alone with his politically cautious White father. Bird’s Asian American mother, Margaret, is a poet whose work has been condemned, causing her to flee the family for their own safety. But as the novel opens, Bird believes he has received a message from Margaret—opening the door to a very different life. In a starred review, Kirkus calls the novel “taut and terrifying.…[It] underscores that the stories we tell about our lives and those of others can change hearts, minds, and history.” This week, the novel was selected by Reese Witherspoon for her popular book club.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

I love a book that probes political questions and ideas but does so with a lot of heart and feeling. I always want my emotions to be engaged, and I’m grateful when a book can give me both those things, which yours did.

I’m glad to hear it, because that’s how I am, too. I love books of ideas—what books aren’t books of ideas?—but I always need an emotional connection. And I need an emotional connection before I can find my way into [writing] a book. This one for me is really a parent story. It’s the story about this mother and son in particular, and then this family in general. And that was my way in. And all the other stuff came after that.

You mean the political dimension of the story?

There was so much happening in the outside world that it was creeping into the document. It felt like we were living in a dystopia, and to make sense of it, I needed to write into that dystopia.

Was that a genre you felt comfortable writing?

I read pretty widely, and I’ve read books that are dystopian, but I don’t think of myself as that kind of writer. I didn’t really know what to do. But I thought of Margaret Atwood’s famous dictum that when she was writing The Handmaid’s Tale, she chose not to put anything in the book that didn’t have a precedent in some way in the real world. I tried to take that as my guiding principle, because I didn’t want people to be able to say, That’s completely made up. All the things that I put in the story have some root in what’s happened before or what’s happening now. It’s not exactly a dystopia—it’s where we are but dialed up maybe two notches. It’s a place where we might be heading, and I hope not, but it felt eerily close to me. And I’m hoping it’ll feel that way to readers, too, so they’ll start thinking, Is that where we want to go? Can we do anything about it?

We start with Bird’s perspective. He’s 12, and he has a 12-year-old’s perspective on his family, on world events. Why did you want to begin there?

I always thought of the book as an opening out. If we start off with Bird’s perspective, a child’s perspective, it’s quite limited because of what he’s been exposed to. He’s been sheltered on purpose, right? And of course, because he’s a child, he doesn’t have the context and doesn’t even have the vocabulary to explain what’s going on. And he’s pulled out from his very small dorm—literally in a tower at a university—and he’s moved out into the wider world. I wanted this to mirror the opening-up that happens to you in adolescence. Adolescence has always been a really interesting period to me because you have a lot of capability, but you don’t have a lot of agency. Your body is turning into an adult, but your mind is not necessarily adult. Then when we move into [his mother] Margaret’s perspective, in the second part of the book, it’s an outward movement; we’re getting the sense of Bird’s family. And then in the third part, we zoom out even further; we’re now able to move around in time and space, and we can get a wider perspective. My hope is that the reader takes that journey along with Bird.

I always thought of the book as an opening out. If we start off with Bird’s perspective, a child’s perspective, it’s quite limited because of what he’s been exposed to. He’s been sheltered on purpose, right? And of course, because he’s a child, he doesn’t have the context and doesn’t even have the vocabulary to explain what’s going on. And he’s pulled out from his very small dorm—literally in a tower at a university—and he’s moved out into the wider world. I wanted this to mirror the opening-up that happens to you in adolescence. Adolescence has always been a really interesting period to me because you have a lot of capability, but you don’t have a lot of agency. Your body is turning into an adult, but your mind is not necessarily adult. Then when we move into [his mother] Margaret’s perspective, in the second part of the book, it’s an outward movement; we’re getting the sense of Bird’s family. And then in the third part, we zoom out even further; we’re now able to move around in time and space, and we can get a wider perspective. My hope is that the reader takes that journey along with Bird.

Early in the book, we don’t know a lot about Margaret. We know that she’s a poet and that she has become a symbolic icon for the resistance. And we learn that this happened in an almost accidental way, not deliberately.

I was really interested in the idea that as a creative person, your work takes on a life of its own, and at a certain point it’s no longer up to you to decide the meaning of your work. Its meaning is decided by the people who engage with the work. Margaret wrote a poem. She thought it was about one thing; it became interpreted by one group as an emblem of resistance, and it became interpreted by another group as a clear sign that she was a threat and danger. And yet, for her, it had this very different, very personal meaning. And a lot of times that’s how art works.

Is there anything else you’d like people to know about Our Missing Hearts?

Even though it does take place in this very dark world, it is for me, fundamentally, a book about hope and about love, which sounds cheesy when I put it that way. But I wrote the book because I am a parent, I am a person in the world. The past three years have not been great. And I’ve been asking myself, How do you keep going? How are you supposed to raise the next generation when it feels like the world is falling apart? I was looking for reasons to keep going, and that was the quest that I think the characters in the book have: Why should you keep fighting? We always think about fighting against something. Well, what are you actually fighting for? What are the reasons for hope and to keep going? I think we need those; I’m looking for books that point me in that direction.

Tom Beer is the editor-in-chief.